Texas Longhorns Return to Copperas Cove

By MISCHA BAEZA

Special to Leader-Press

After nearly a century and a half, the first of a growing herd of Texas Longhorns have returned to Copperas Cove, or more specifically to the historic Powell Ranch located on the western edge of the city limits west of Bea Powell Road.

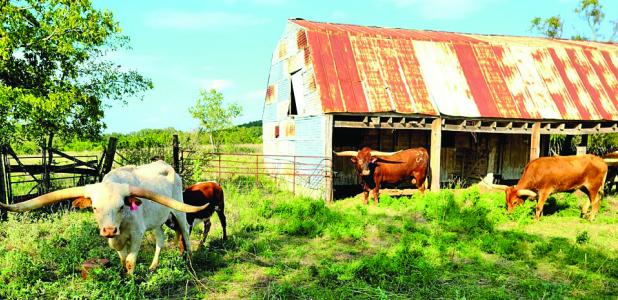

Two registered Longhorn cows, Lil’ Gypsy Eagle and her sister, Pretty Awesome, along with warily eye rancher, Glynn Powell, can be seen from a respectful distance. Other Longhorns are more interested in the knee-high grass.

Their ancestors first set foot on American soil almost 500 years ago, Today, these ladies are products of “survival of the fittest”. Shaped by a combination of natural selection and adaptation to the environment, Texas Longhorns are the only cattle breed in America which are truly adapted to America.

The era of cattle drives began in 1866. Destined for Kansas, huge herds of Longhorns were grazed from South Texas to about where Round Rock is today and then the famous Chisholm Trail divided. One branch of the trail ran through Belton – you can still see the wagon tracks at Camp Tahuaya – and the other one went more westerly through Lampasas.

Copperas Cove and the Powell Ranch were in the middle with plentiful native prairie grasses such as Indian Grass, Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, and Switch Grass for the grazing herds.

Deed records show that the Powell Ranch was originally owned by W.H. Davis who received it in 1838 as a land grant from the Republic of Texas for his service in the Texas Revolution at the Battle of San Jacinto. Wild mustangs, Longhorn cattle and migrating buffalo grazed here. However, Davis never resided on the property because, at the time of his ownership, it was still a part of the Comanchería.

Cove’s early German settlers arrived while Comanche sign and buffalo bones were still fresh and wild Longhorn cattle roamed on the open grassland. Joe Kattner’s family probably ate the last Longhorns and stretched the first barbed wires across what is now the Powell Ranch prior to the arrival of the railroad in 1882.

Settlers like the Kattners, with their plows and barbed wire, ended to the cattle drive era and almost eliminated Longhorns entirely. Fortunately, beginning in 1927, the Texas Longhorn was preserved by the United States Government on wildlife refuges in Oklahoma and Nebraska.

Bea Powell (pronounced “bee”), the namesake of Bea Powell Road, purchased the property in 1947.

Ownership of the property passed from Bea and Verna to their sons and eventually to Glynn Powell and his family. Glynn’s wife and high school sweetheart, Dorothy, is a direct descendant of Joe Kattner, creating a combined family heritage in the property extending back in time nearly 150 years.

Today, the ranch is managed by Glynn Powell, a former Copperas Cove ISD teacher, administrator, and trustee. Powell is also a certified vocational agriculture teacher, lifetime cattleman and conservationist. Glynn and Dorothy both graduated from Copperas Cove High School as did their children and a growing number of grandchildren.

Farming and ranching in central Texas has always been a family affair. Things are no different today. On most weekends, Glynn prepares a hearty predawn farm breakfast for their children and early rising grandchildren – the “top hands”– who generally welcome the opportunity for ranch work.

Dorothy enjoys rewarding her cowhands with a late lunch that often includes traditional cowboy fare like pinto beans and cornbread.

“Ranching teaches resilience, and I cannot think of a better place for these kids to be during a pandemic than outside working,” she said.

Daughter and son-in-law, Karen (Powell) and Raymond Harrison, both internal medicine physicians, are often among Dorothy’s “kids” seated around her table as are son and daughter-in-law Blake and Maggie Powell along with varying combinations of grand kids, the “cow hands.”

For Dr. Karen Harrison, ranching has changed in some ways and, in other ways, it has remained much the same as it was for her ancestors.

“Today, we use drones, GPS, and mobile computer apps to locate specific points on the ranch and enjoy modern equipment with air-conditioned cabs,” she said. However, uncertain weather conditions, labor required to construct fences, and hazards of working with large animals remain unchanged.

“I remind our family, guests and neighbors that Longhorn cattle can be dangerous. Never approach a Longhorn that is unfamiliar with you and especially one with a new calf. Has our hospital treated people injured by Longhorns? Yes. So, be careful.”

From Glynn Powell’s perspective, central Texas presented challenges to survival for early settlers that are difficult to imagine today.

“I would not trade places with them,” Glynn said. These are strong words considering Powell is no stranger to hardship himself. When his family purchased the property, they had reasonable expectations of rainfall previously experienced.

Weather conditions proved much harsher than they could have ever imagined. The Bea Powell Family survived and overcame the severe 1950s Texas drought, a period between 1949 and 1957 in which the state received 30% to 50% less rain than normal, while temperatures rose above average.

During this time, central Texans experienced the second-, third-, and eighth-driest single years ever in the state – 1956, 1954, and 1951, respectively.

Bea Powell stewarded the property for nearly half a century, constructing new fences, windmill, barns, soil conservation water tanks and a new home. Bea, Verna and sons Glynn and Landis survived by raising beef cattle, goats, hogs and chickens and cultivated corn, sorghum, and hay despite extremely dry conditions. Bea introduced mechanized farming in the form of a 1942 Ford Model 2N tractor. He even removed timber on top of Powell Mountain by dragging a ship anchor chain between two bulldozers in 1956.

Bea Powell passed away in 1991. In succeeding decades, fences and improvements deteriorated and cedar persistently invaded previously cultivated fields and meadows. A couple months into the global pandemic with businesses and schools closed, Glynn decided the time was right to remove and replace over four miles of bad fence.

Three generations of Powells and Harrisons rolled up their sleeves and went to work. Six months later, they stretched the last strands of barbed wire. New gates were welded and hung, barns repaired, and long dry water troughs bubbled back to life.

“No one took a vacation this year,” reflected Blake Powell, attorney and rancher. “Our kids really stepped up and worked hard cutting brush, digging post holes, mixing concrete, and stretching wire. Two of our boys even worked on what should have been their graduation day. They all collected a few cuts, bruises, and blisters but—knock on wood—so far, not one has caught the Coronavirus. I’m really proud of this whole bunch. Hard work is a part of their heritage and they are growing into topflight cow handlers.”

With perimeter fences replaced, Glynn Powell’s focus turns to conservation.

“Circumstances compelled early settlers to plow every acre they could and overgraze the rest. Consequently, many native prairie grasses and forbs disappeared. What we see today is only a fraction of the diversity of native species originally found here and we aim to change that,” Powell said. “Our goal is to restore native species and natural ecology. We are in contact and plan to partner with the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service to eradicate invasive species such as Ashe juniper and re-introduce native species of grasses and forbs. We also seek to collaborate with the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department to manage existing wildlife species more carefully.

Texas Longhorns fit this plan perfectly because Longhorn cattle eat a wider range of grasses, plants, and weeds than most other cattle. This permits us to use less fertilizer and weed killers than we would with other breeds of cattle.”

“Can we talk about steak?” asked a beaming Maggie Powell. “In addition to fitting our conservation plans, these cattle are a delicacy,” she added. Longhorns produce a very lean beef. She even considers this lean beef a super food.

“If you pair a Texas Longhorn steak with some leafy greens, mushrooms and a sweet potato and you are eating well and yes—you’re smiling because it tastes so darn good!” Maggie said.

Studies have shown that Texas Longhorn beef is significantly lower in cholesterol than other breeds of beef cattle.

A Texas Longhorn raised on grass without chemicals or supplements, produces meat that is lower in cholesterol than a skinless chicken breast.

“I feel good knowing we are producing a heart-healthy product. Not only are we growing cattle that look great, we are also producing the healthiest and best tasting premium beef on the planet,” said Glynn. “We feel blessed in knowing that we are helping people to live longer, healthier lives while preserving a living symbol of the Old West.”

How are those living symbols of the Old West adjusting to their new home? Lil’ Gypsy Eagle and her sister, Pretty Awesome, just seem happy to be back home and grazing on tall grass again in Coryell County.